If all this time you were thinking coronavirus is just a respiratory disease, think again. Scientists have been able to uncover a lot about the novel disease, six months into its inception, and now it is becoming increasingly clear that coronavirus can also trigger a wide range of neurological problems.

Several studies have underlined that not only does COVID-19 damage the lungs, heart and kidneys, it can also cause severe brain damage – with patients suffering neurological conditions including paranoia and hallucinations. At the outset of the pandemic, the first salient finding this domain was the loss of taste and smell amongst those suffering from the disease. Now, more than 300 studies from around the world have found an occurrence of neurological abnormalities in COVID-19 patients, including mild symptoms like headaches, loss of smell (anosmia) and tingling sensations (arcoparasthesia), up to more severe outcomes such as aphasia (inability to speak), strokes and seizures.

It has also been observed that severity of lung illness does not always correlate with the severity of neurological illness. These complications can occur up to six days before and 14 days after the onset of the more common Covid-19 symptoms such as a dry cough or fever.

There are increasing pieces of evidence that the novel coronavirus impacts the central nervous system leading to neurological symptoms. The receptor which allows Covid-19 to enter cells is present not only in the respiratory tract, but it is also present in cells of other organs, such as the brain and liver. For viruses like coronavirus, it’s common for them to be able to mitigate.

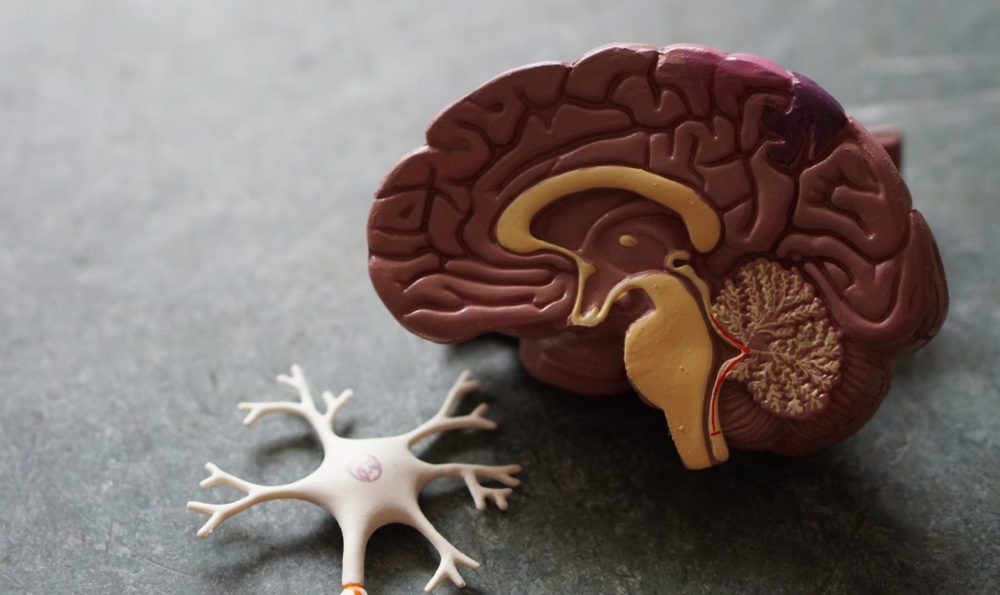

When it comes to the brain and nerves, coronavirus appears to have four main sets of effects:

- A confused state and disorientation. People with Covid-19 have reported to experience delirium and confusion. There have been several speculations pertaining to COVID-19’s effect on the brain, including a decline in cognition leading to worsening of pre-existing neurological conditions like dementia.

- Inflammation of the brain. According to a study published in The Lancet Psychiatry, almost half of the 125 coronavirus patients admitted in the UK hospitals suffered from brain inflammation. Inflammation of the brain includes a form showing inflammatory lesions – acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) – together with the effects of low oxygen in the brain.

- Blood clots leading to stroke. Part of the trigger for the strokes was a massive overreaction by the immune system which causes inflammation in the body and brain. Many COVID-19 patients with severe illness develop blood clots in intensive care, even after they are put on blood thinner drugs. Growing evidence suggests that some of the major complications of the coronavirus disease could be caused by blood clotting.

- Potential damage to the nerves in the body, causing pain and numbness like in the form of post-infectious Guillain-Barré syndrome, in which your body’s immune system attacks your nerves.

While about 80% of people who develop Covid-19 are able to shake off the virus easily, a small percentage quickly worsen and within days die from respiratory weakness and multi-system organ failure. Many of these patients are elderly or have underlying health conditions, but not all. Coronavirus has made itself clear that it is extremely heterogeneous in its manifestation. The disease affects many different organ systems: patients can die not only from lung failure, but also kidney failure, blood clots, liver abnormalities, and neurological manifestations. Evidence is starting to accumulate demonstrating that the virus can cross the blood-brain barrier. Some scientists also suspect that the virus causes respiratory failure and death not through damage to the lungs but through damage to the brainstem, the command centre that ensures we continue to breathe even when unconscious.

Coronavirus and brain damage

Our brain is shielded from infectious diseases by what is known as the “blood-brain barrier” – a lining of specialised cells inside the capillaries running through the brain and spinal cord. These block microbes and other toxic agents from infecting the brain. If the novel coronavirus crosses this barrier, it suggests that not only can the virus get into the core of the central nervous system, but also that it may remain there, with the potential to return years down the line.

Although the virus’ impact on the lungs have been the most immediate, its lasting impact on the nervous system can be far larger and more devastating.

Since the start of the pandemic, it has become increasingly clear that Coronavirus is not just a turbocharged version of the virus that causes the common cold: it has a number of unusual and sometimes terrifying traits.